WWII Veteran a Living Witness to History

Originally published by Alistair Steele for CBC News, November 10 2021

On Remembrance Day, and most other days, Second World War veteran Ron "Shorty" Moyes thinks of the thousands of Canadian airmen who never made it home.

He thinks of one man in particular, though they never met.

"I think of him. I wonder if he made it all right or what happened."

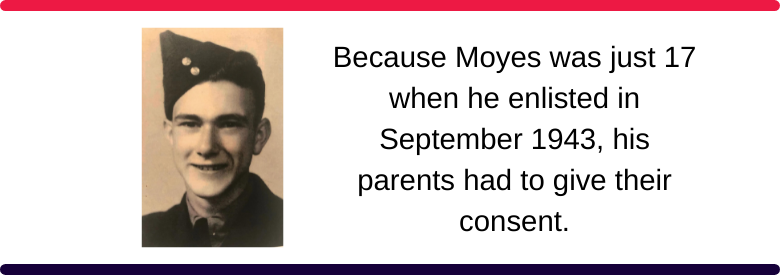

Now 95, Moyes was just 17 and living on his family's farm in Coquitlam, B.C., when he decided to leave school and follow his big brother Horace into the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF).

It was September 1943, and the air war over Europe was in full swing. His parents gave their consent, and off the teenager went to basic training in Edmonton.

Training continued in Quebec, where Moyes graduated as a sergeant air gunner the following spring. With his new rank came a pay raise, from $35 a month ($15 of which went home to his parents for safekeeping) to the relatively rich sum of $3 a day.

In May 1944, Moyes and about 80 other gunners shipped out from Halifax. It was no pleasure cruise — their quarters were canvas lean-tos on the ship's top deck, where they slept in narrow, stacked bunks. They were ordered to man the vessel's anti-aircraft guns, a critical job since the troop ship, with 3,000 souls aboard, had no escort across the Atlantic.

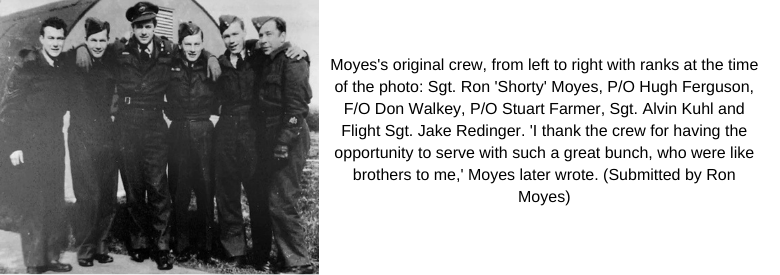

Once safely in England, Moyes was sent to an operational training unit in Nottinghamshire, where the gunners were "crewed up" with the pilots, navigators, bomb aimers, wireless operators and engineers with whom they were to spend the rest of the war.

It was Flying Officer Don Walkey who gave Moyes the nickname he'd keep for life.

"My pilot was six-foot-two. He said, 'Hi Shorty,' and that was it. The children and the grandchildren still call me Shorty. I haven't grown any!" Moyes joked.

'You OK, Shorty?'

The six-man crew trained together in a twin-engine Wellington bomber until September. They were then sent to another base for instruction on "escape and evasion," including how to hide parachutes after bailing out, and the best way to approach a farmhouse behind enemy lines.

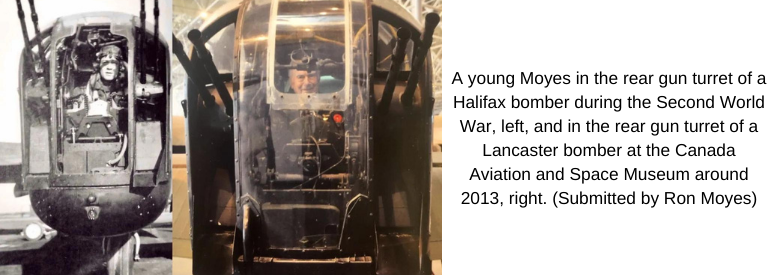

The crew soon began training on the four-engine Halifax bomber and was transferred to 429 Squadron at RCAF Station Leeming, near York. On Nov. 16, they received orders for their first bombing mission to the town of Jülich in the industrial Ruhr region of western Germany.

There were no comfortable seats on a Halifax, but the rear gunner's was perhaps the least commodious. With the Plexiglas windshield cut out for better visibility, winter temperatures at 5,000 to 6,500 metres could drop to –50 C. To stay warm, Moyes wrapped himself in a nearly impossible number of layers, including an electrically heated suit.

"It's all very well unless you have to go pee. We climbed into the turret and you don't get out till you land," Moyes said.

He was also isolated from the rest of the crew, sometimes for eight hours at a time. Every 30 minutes, Walkey would check in over the radio, asking, "You OK, Shorty?"

In fact, it was incredibly dangerous work: tail gunner on a heavy bomber is commonly said to have been the single deadliest job on the Allied side during the war. This was especially true after enemy fighters learned to attack from below, igniting the bomber's fuel tanks or detonating its payload.

The crew's first bombing mission was Moyes's first experience with anti-aircraft shells, or flak, which he likens to the sound of "somebody throwing stones" at the fuselage. Often, the extent of the damage couldn't be assessed until they'd returned to base.

"You never know how your undercarriage is until you land, so that was always a worry," Moyes recalled.

30 missions

That mission was a success, the first of 30 for the crew, half aboard the Halifax and half aboard a Lancaster bomber after their transfer to an elite Pathfinder squadron. There were plenty of close calls along the way, however.

In late December, on another night raid over the Ruhr valley, the crew was heading home when they picked up two German fighters. As the smaller planes worked in tandem to bring the bomber down, Walkey had to employ an evasive "corkscrew" manoeuvre, ducking in and out of clouds. This continued for an hour until the bomber neared the English coast and the fighters gave up the chase and turned back.

I'll tell you now that I sure prayed we'd make it out of there. I imagine the rest of the crew did the same.- Ron Moyes

That New Year's Eve, on a mission to Norway — they'd been tasked with dropping mines with altered fuses into shallow water to confuse the Germans — unseen anti-aircraft guns suddenly opened up from close range.

"We closed the door and all hell broke loose. You couldn't see the sky for tracer [fire]. The ships down there were firing like mad, and we got one big cannon hole right between the wireless air gunner and the navigator," Moyes said.

Moyes and the other gunner kept their fingers on the trigger until their gun barrels were white hot. At one point, Walkey was forced to fly just metres above the surface of the fiord to evade the enemy fire.

"The bomb aimer told the pilot, 'Pull up, I can't swim!'" Moyes said.

It was dawn by the time they reached their base, and Moyes slept through New Year's dinner — a meal he'd been looking forward to for days.

On a night raid over Nuremberg in March 1945, 29 Allied aircraft were lost. "Aircraft seemed to be going down right and left," Moyes later wrote. "I'll tell you now that I sure prayed we'd make it out of there. I imagine the rest of the crew did the same."

Raid on Hitler's mountain lair

On April 26, 1945, the crew — now with 405 Squadron — embarked on their final bombing mission. The target was Adolf Hitler's vacation home near Berchtesgaden in the Bavarian Alps, and the German troops stationed in barracks there.

"Gen. [George] Patton was coming through and he wanted those SS troops out," Moyes said. The crew later learned Hitler hadn't been there when they dropped their bombs. Within days, the German dictator was dead in Berlin.

As the war in Europe wound down, the missions changed. On May 7, Moyes's Lancaster took part in "Operation Manna," dropping food to starving Dutch civilians near Rotterdam. From an altitude of 100 metres, Moyes could see people waving as they ran to pick up the life-saving supplies.

Decades later in Ottawa, Moyes would meet one of those Dutch civilians. "I was on the ground waving at you!" the man told him.

The next day, May 8 — VE-Day — the crew flew to Lübeck, Germany, to pick up allied prisoners of war. On the return trip, against all rules and regulations, Walkey altered his course to fly over London, opening the bomb bay doors to show the freed POWs Buckingham Palace below. Many of the men wept with joy.

Back at the airbase, the Canadians celebrated with wild abandon, firing flares into haystacks and setting the English countryside ablaze. "Of course, the Canadian government probably had to pay for [that] later," Moyes said.

Decades of service

By mid-June 1945, Moyes and his crew were on their way back to Canada. Four of them, including Moyes and Walkey, volunteered to continue fighting in the Pacific theatre, but as they were gearing up to go Japan surrendered and the war ended.

Moyes was discharged that September. He tried his hand at civilian life, but working at a plywood mill was no match for the air force. In September 1946 he rejoined the RCAF, this time as an armorer, later specializing in explosive and bomb disposal. He married Margaret Winters on Valentine's Day 1948, and they had a son and a daughter.

His new career kept the young family on the move, and in 1962 Moyes was posted to a NATO airbase in Zweibrücken, Germany, home to a squadron of nuclear-armed aircraft. This was during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and Moyes was tasked with destroying the base's runway and other infrastructure in the event of a Soviet invasion.

Luckily, that never came to pass, but Moyes did soon count several Germans among his closest friends, making his peace with a former enemy.

The family returned to Ottawa, and in 1974 Moyes was discharged after 31 years with the RCAF to begin a new career as a firearms technician with the RCMP's forensic crime lab. He finally retired in 1989.

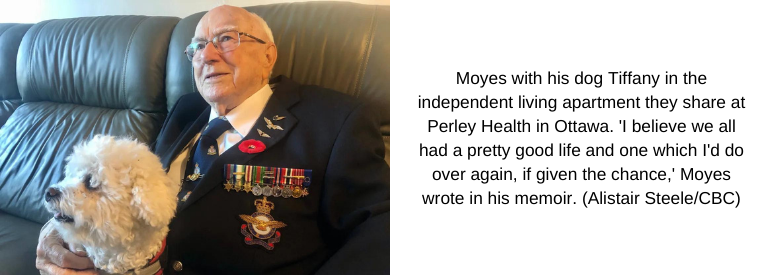

Eventually, the couple moved from their home in Ottawa's Carson Grove neighbourhood into an independent living unit at Perley Health, known until recently as the Perley and Rideau Veterans' Health Centre. Margaret Moyes died last year, and Ron Moyes now lives alone with his bichon Tiffany.

Robert Moyes, who visits frequently and helped compile a detailed account of his father's war years, said he's always been in awe of the constant danger his dad faced as he sat strapped into that gun turret.

"You can't imagine people doing that today," he said. "The conditions back there must have been terrible."

Courtney Rock, director of development for the Perley Health Foundation, said as well as being one of the Russell Road facility's most popular characters, Moyes is also a rare witness to history.

"One of the biggest privileges of working here is having those first-person accounts and those conversations, and I just recognize how fortunate we are to be able to listen to those stories, especially at this time of year," Rock said.

Moyes's bomber crew reunited several times in the years after the Second World War, but Shorty, the youngster among the six, is now the last man standing. He's also one of a dwindling number of veterans still able to recount those harrowing war stories.

As he attends Thursday's Remembrance Day ceremony at Perley Health, Moyes will be thinking of the rest of his crew, and of that unnamed Canadian airman who waved as he drifted toward an unknown fate below.