With Flying Colours

Peter Yarema loves poetry and regularly reads from the favourite volumes he keeps in his room at Perley Health. Now 95 years old, poetry has been a constant in Peter Yarema’s life – a life marked by service to his country, his community and his family. A pilot during the Second World War and Korean War, Yarema later became a highly respected social worker, and a devoted husband and father.

Peter Yarema in uniform

Peter Yarema in uniformPeter’s grandparents and their young children had emigrated from the Ukraine to a Manitoba farm near the hamlet of Teulon, about 60 kilometres north of Winnipeg. Peter’s first language was Ukrainian. The family later moved to Sarto, another Manitoba farm community, and Peter attended a French school, where he soon acquired a passion for the language.

As an adult, he revelled in French poetry, plays and philosophy, an interest he tried in vain to inspire in his children. “The children would joke amongst ourselves that when dad would reach for a book of poetry or plays, it was time to run and hide,” recalls John, the eldest of three children.

When the war broke out, Peter enlisted in the Royal Air Force; at the time, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) was tiny, although it grew exponentially over the next seven years. Peter joined the RCAF for his third tour in Europe.

During the Second World War, Peter Yarema flew a wide variety of aircraft: from the tiny, open-cockpit Tiger Moth to the Lancaster, a four-engine behemoth. His assignments also varied considerably: from ferrying empty planes, equipment and troops, to bombing runs and reconnaissance missions. Although he often came under enemy fire, the most harrowing moment was when a flare went off in the cockpit – somehow the navigator was able to throw it out before it caused a crash.

DH98 Mosquito

DH98 MosquitoDuring 1944 alone, Peter completed more than 50 bombing missions over Germany. On these missions, he served as a pathfinder: piloting a fast, twin-engine Mosquito, he and a navigator/bomb-aimer would drop flares to mark targets for formations of bombers. Like most pilots, he was daring and brave.

Peter flew with the same co-pilot dozens of combat missions; after their last flight together, the copilot stormed off without saying goodbye because he felt Peter had put their lives in danger too often. Approximately 10,000 Canadian airmen died during these bombing missions.

Margaret Yarema (née Sootheran)

Margaret Yarema (née Sootheran)While stationed in England, he met a woman on a train: Margaret Mary Sootheran served in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force at Bletchley Park, the legendary headquarters for British codebreakers. Born into a wealthy family, Margaret had attended Queen Ethelburga’s Collegiate, a swank private school.

The Sootheran family was not impressed when their daughter announced her intention to marry a Canadian farm boy, even if he was a pilot. Six weeks after meeting, Margaret and Peter married; both then returned to their wartime service.

Peter Yarema’s service earned him a Distinguished Flying Cross, although he wasn’t aware of the honour until years later. When medal and citation arrived at the family home in Manitoba, Peter’s mother – who spoke little English – stashed them away in a drawer, perhaps unaware of their importance.

“I don’t remember much about the war now,” says Peter. “I’m 95 and I’ve forgotten most of it. He remembers, though,” gesturing to John, the eldest of his three children. “Dad didn’t talk a lot about his wartime service when we were kids,” says John Yarema, now retired and living in Winnipeg. “In recent years, I’ve been trying to piece it all together and it’s been fascinating.”

During a recent visit, father and son pored over Peter’s pilot logbooks, trying to decipher the lists of acronyms and numbers that document hundreds of flights and thousands of flying hours in more than a dozen different aircraft.

After the war, Peter Yarema earned his teacher’s certificate, but the work didn’t suit him and he re-enlisted. During the Korean War, he ferried personnel and equipment between Seattle, Japan and Korea. Along the way, the family grew: after John came Anne and Sarah. The family eventually settled in Ottawa.

“My dad is a loving, practical and reliable man,” says daughter Sarah. “I have fond memories of dozing off on the couch on cold winter afternoons with him reading poetry aloud.”

When Canada scaled back the RCAF in the mid-1960s, Peter was laid off and soon began a new career as a social worker. Initially, he found it difficult, but eventually became known as one of the best and was often assigned the most difficult cases.

“I met him 1975, when I was starting my first real job,” says Barbara Merriam, a work colleague and long-time friend who visits Peter regularly. “For years, we shared brown-bag lunches – Margaret would make dessert for both of us. Working with troubled families can rip your heart out, but Peter was somehow able to shield himself from that – perhaps in the same way that he

learned to cope with his wartime experiences.”

Peter and Barbara share a love of poetry, plays and French philosophy. Together with Margaret Yarema, they loved to downhill ski and skate the Rideau Canal. Although eligible to retire at age 65, Peter continued to work for another eight years.

“During the latter part of his career, judges and other court officials often asked for his advice on difficult cases,” recalls Barbara Merriam. “He was highly respected.” Many summers, the Yarema family would pack up their tent trailer for extended camping trips.

Peter and Margaret remained active during their golden years – Peter biked into his 90s and volunteered as a driver for a local seniors’ organization until he gave up his licence at age 92.

Son John remembers taking his father to the Canadian War Museum in 2007, when an exhibit about Bomber Command touched off a national controversy. The panel questioned the Allies’ attempt to bomb Germany into submission from the sky.

Many Veterans criticized it as revisionist history and the Museum eventually changed the text. By late 1943, the Allies had gained control of the skies, but the Nazis exerted ruthless control over most of Europe. Bomber Command hoped to destroy

Germany’s industrial capacity; and while the effort achieved some success, it came at a significant cost: dozens of cities destroyed, and hundreds of thousands of German civilians killed, along with tens of thousands of Allied airmen.

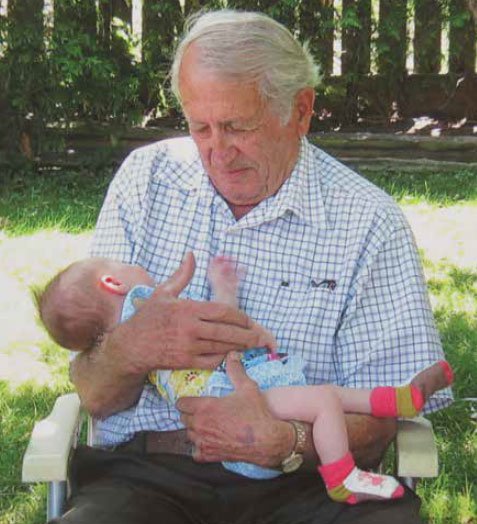

Peter Yarema and great-grandaughter Cecilia

Peter Yarema and great-grandaughter Cecilia“Seeing the exhibit with my dad was almost overwhelming,” says John Yarema. “He told me that there was no such thing as precision bombing in the 1940s and the role he had played in the deaths of so many people broke his heart.”

In their later years, Peter and Margaret took comfort in their four grandchildren and one great-grandaugher. Margaret passed away in 2014 shortly before their 70th wedding anniversary; Peter, unable to cope on his own, moved into Perley Health a few months later. He receives frequent visits from family, Barbara Merriam and friends from a theatre group. And he still loves to immerse himself in poetry.