The determined war effort of Ottawa's Bill Gunter

By Andrew Duffy, originally published November 10, 2022

Ottawa’s Bill Gunter was just 14 when the Second World War began in September 1939, but he was hellbent on getting involved.

He immediately joined the Sea Cadets, a youth training program, and one year later, at 15, enlisted in an army reserve unit even though recruits were supposed to be 18. He trained as a soldier for one summer before being forced to produce his birth certificate: Gunter was quickly discharged when officers discovered his real age.

Not easily deterred, Gunter took his discharge certificate, marched over to another army reserve unit, and promptly re-enlisted.

The next year, 1942, he joined the Royal Canadian Navy since it was the only service branch that accepted 17-year-olds. It meant Gunter was finally a legal member of the Canadian Armed Forces.

“I just couldn’t wait,” he says of his determination to enlist. “It was an exciting thing to do, as exciting as you could get.”

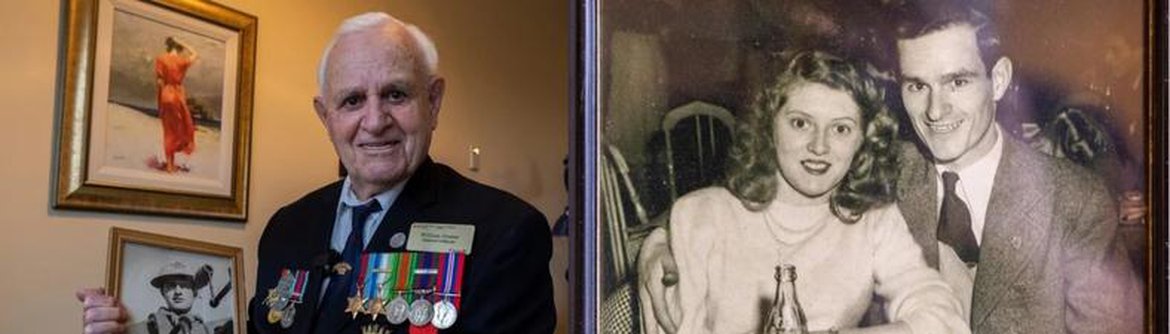

Now 97 and living in an apartment at the Perley Health facility in Ottawa, Gunter recently reflected on his Second World War experience: He is among precious few Canadians who can still offer a first-hand account of D-Day, the largest seaborne invasion in history.

He served as an able seaman and gunner on a large landing craft that delivered 192 soldiers to the beach at Bernières-sur-Mer on the morning of June 6, 1944.

“All the other landing craft were helter-skelter all over the beach,” he remembers, “and there was machine gun and mortar fire.”

William “Bill” Gunter grew up in Sandy Hill, the middle child in a family of five. His father, a First World War veteran injured at the Somme, worked as a civil servant.

Gunter attended Ottawa Technical High School and held a part-time job as a delivery boy for a local pharmacy. He often delivered drink mix to First World War flying ace Billy Bishop — he lived at 5 Blackburn Avenue during the Second World War — one block away from Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, who lived in nearby Laurier House.

“Oh, he was a tightwad,” Gunter says of King. “He wouldn’t give us anything on Halloween.”

Gunter’s eldest brother, George, joined the Royal Canadian Navy months after the outbreak of the Second World War, and would become one of its more unusual casualties. George Gunther died in a fall down an elevator shaft at Canadian Naval Headquarters on Queen Street while working the night shift on Feb. 8, 1941. He was 22.

His brother’s death did not deter Gunter from joining the navy the following year. He trained in Montreal for two months before being sent to Halifax, where was one of 10 young men who volunteered to serve in a British combined forces commando group under Lord Louis Mountbatten. The commando group was tasked with making raids on German-occupied coastal areas.

Gunter was sent overseas to train in England and Scotland; he learned to operate a small landing craft as part of a three-man crew that could deliver about 30 soldiers to enemy shores.

But as planning for D-Day began, Gunter was sent to gunnery school and re-assigned to a Landing Craft Infantry (Large), a vessel big enough to make its way across the English Channel.

During the dark early morning hours of June 6, 1944, Gunter was at the helm of LCI(L) 249. The landing craft did not have a ship’s wheel so Gunter had to steer using electronic controls. He was never sure what the rudder was doing.

“We went zig-zagging from England to France,” he says.

As the landing craft neared the Normandy coast, Gunter took up his position at the trigger of a 20-mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft gun. The landing craft surged toward Bernières-sur-Mer at top speed, struck a mine that damaged its port side, and plowed into the sandy bottom.

Many of the flotilla’s other landing craft were similarly damaged by mines and other obstacles as they approached the beach.

Gunter’s landing craft was in the second wave of the D-Day attacks on Juno Beach, and the Germans continued to put up stiff resistance. The mine did not injure any of those on board, but it meant the soldiers had to disembark into deeper water than they had planned and fight to get their equipment ashore.

After disgorging its cargo of soldiers, LCI(L) 249 was towed back across the English Channel. It continued to ferry troops across to France after some repairs.

In all, more than 6,000 naval vessels took part in D-Day, including battleships, destroyers, minesweepers, escort ships and landing craft. They delivered 132,000 troops to the beaches of Normandy in a single day.

Gunter was stationed back in Halifax when Victory in Europe was announced on May 7, 1945. He avoided the riots that broke out in Halifax – and destroyed hundreds of downtown businesses – because he was soon to be married.

“I had to behave myself because I was trying to get leave, and I didn’t want to get mixed up in the antics downtown,” he says.

He married Ottawa’s Shirley Poapst on June 1, 1945. After Gunter was discharged from the navy, he settled into a career in the Department of Finance, where he worked as a treasury officer. He raised three children with Shirley, and they retired to a life of golf, skiing, sailing and travel.

Gunter travelled to Normandy to mark the 50th, 60th and 70th anniversaries of the D-Day landings, and walked with Prime Minister Stephen Harper on the beach at Bernières-sur-Mer. In April 2015, France made Gunter a knight of the Legion of Honour.

He moved into Perley Health after his wife, Shirley, died in May 2021. They were married for almost 76 years.

“She was bright and beautiful,” he says. “I was very lucky.”