Korean War Veteran Remembers "The Forgotten War"

Originally published by Andrew Duffy for the Ottawa Citizen, November 10 2021

When Sheridan “Pat” Patterson was a boy growing up on a farm in Burk’s Falls, north of Huntsville, a Canadian army unit rolled into town one day to put on a demonstration.

The soldiers performed some foot drills, charged up a hill with fixed bayonets, and fired their two artillery pieces. Patterson, who milked the cows every morning before going to a one-room schoolhouse, was enthralled.

“I thought, ‘Now that’s something to get doing,’” he remembers. “I said, ‘That’s for me.’”

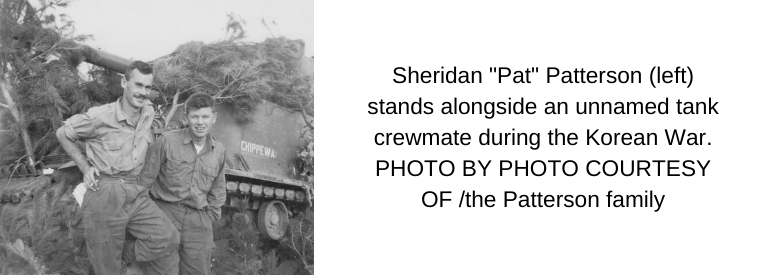

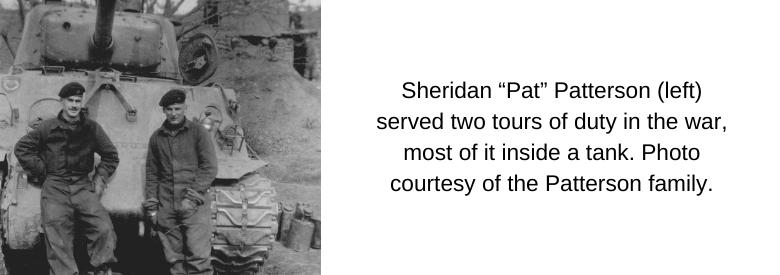

Patterson, now 92, would eventually join the Canadian army and serve two tours of duty on the front lines of the Korean War. First, though, he would endure personal tragedy.

When Patterson was in Grade 8, the family’s barn burned to the ground, taking with it the family’s livelihood. Soon after, his mother succumbed to cancer.

Patterson was sent to Toronto to live with an aunt while his father went to work as a lumber camp blacksmith. Unhappy in Toronto, Patterson returned a few years later and went to live with his father in the lumber camp.

“I went to where he was, and he said, ‘Get a job.’ So I ended up at one end of a crosscut saw,” remembers Patterson.

At 16, he spent one miserable winter cutting trees in the bush: “When I come out of there in the spring, I said ‘I’m never going back.’”

He joined the army. Patterson trained as a tank gunner, driver, radio operator and gun loader, and was eventually assigned to CFB Petawawa.

In June 1950, the Korean War broke out when 100,000 North Korean troops streamed across the border in an attempt to reunite the country, which had been divided at the end of the Second World War into a communist northern half and U.S.-occupied southern half.

In response to the invasion, the United Nations authorized member states to provide military assistance to South Korea, and in August, the Canadian government announced it would send troops.

At CFB Petawawa, the commanding officer asked for volunteers to serve in what was then known as the Canadian Army Special Force (it would later be named the 25th Canadian Infantry Brigade Group) in Korea. Patterson stuck up his hand.

“I wanted to get into that,” he remembers. “I wanted to test myself: Do I have the guts to do this?”

He trained for six months in Fort Lewis, Washington, boarded a U.S. troop ship, and arrived in Busan, South Korea, in May 1951. Along with other members of “C” Squadron of Lord Strathcona’s Horse, an armoured regiment, Patterson was sent north of Seoul to the front lines.

There, the Canadians attacked a steep hill near the village of Chail-li held by well-entrenched Chinese forces that had entered the war to fight with the communist north. Patterson experienced combat for the first time, and helped evacuate some of the attack’s five dead and 31 wounded Canadian soldiers.

“That was the beginning of it,” he says.

Patterson had some harrowing experiences in the war. While on a patrol in no-man’s land near the town of Ch’orwon, a mortar round hit the front of his tank. Patterson was looking out of the tank’s open hatch and heard the round coming towards them.

“I just remember saying to the guys, ‘Geez, this is a close one,’” he says.

The driver suffered serious shrapnel wounds to his head and had to be evacuated. The incident scarred another member of the tank crew who later attacked Patterson for keeping the tank’s main hatch open during another mortar attack. Patterson wanted light from the open hatch to read.

“Guys do crack from that mortar fire,” he says.

Later, during another patrol, Patterson’s tank hit a buried mine, which blew one row of the tank’s wheels off the vehicle and warped its hull. The crew scrambled out of the crippled tank in fear that its fuel would ignite. “We were all bleeding from the nose and ears,” he says.

The most intense fighting he experienced, Patterson says, was at Hill 355, a hotly-contested piece of high ground that was periodically shelled and attacked by Chinese forces.

Early in the Korean War, major offensives were conducted by both sides as armies moved up and down the peninsula. In mid-1951, however, they settled into defensive positions near the 38th parallel while peace negotiations plodded along. They would conclude with an armistice in July 1953.

Patterson’s war ended when he contracted malaria, which sent him to a Red Cross hospital, then back to Canada in late 1952. “My dad was some glad to see me home: I think him and I went beer drinking,” he says.

Patterson served 31 years in the military, retiring as a master warrant officer from the regular force in 1978. He then became a cadet instructor and finished his career as a major in the Canadian Forces Supplementary Reserve.

Patterson met his wife soon after the Korean War while stationed in Calgary. He had to attend a formal dance in the Sergeants’ Mess and was required to escort a woman, but Patterson was at a loss until he remembered that his uncle had two young women living as boarders in Calgary. He asked his relative to choose a date for him.

“I took her to the dance that night and married her a couple of months later,” Patterson says. “Her name was Gwynneth, and she was the finest girl that ever set foot on this green Earth.”

They raised two sons — Mike and Kevin Patterson would both become Canadian Forces combat engineers — while moving 19 times across Canada and Germany. Patterson moved into a room at Perley Health in Ottawa after Gwynneth died last November.

More than 26,000 Canadians served during the Korean War; 516 of those soldiers died and about 1,200 were wounded. Some call it “the forgotten war” because it received so little attention compared to the other major conflagrations of the 20th century.