Ahead of Her Time

By Peter MacKinnon

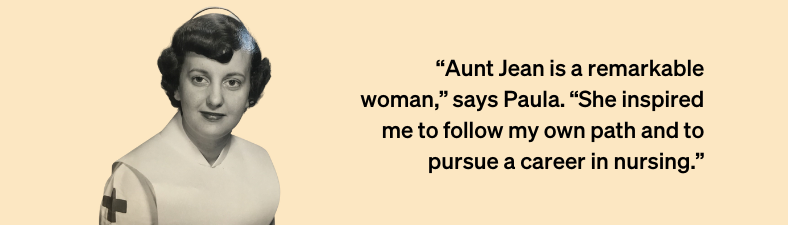

Jean Tait devoted much of her life to improving the lives of disabled children and their families. Along the way, she helped blaze a trail for future generations of women such as her niece, Paula Moore.

“Aunt Jean is a remarkable woman,” says Paula. “She inspired me to follow my own path and to pursue a career in nursing.”

Born Mary Jean Tait in Brockville in 1930, she was the first in her family to study past high school. Jean attended the nursing program at Kingston General Hospital and became a Registered Nurse (RN) at the age of 20. When her sister Isabelle went into labour a few years later, Jean attended the birth of her niece, Paula.

“For most of my life, Aunt Jean has been like a second mother to me,” says Paula. “Our relationship has evolved quite a bit over the years, but we’ve always been there for one another.”

An excellent RN— particularly in the care of children—Jean eventually became head nurse of Kingston General Hospital’s pediatric unit. At the time, pediatrics was a relatively new specialty; the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada certified its first pediatrician in 1943. A major focus of medicine during the era was polio, a virus that can cause permanent paralysis and death, particularly among children. In Canada, the disease peaked in 1953, with nearly 9,000 cases and 500 deaths. Jean Tait devoted much of this part of her career to caring for polio victims and to the vaccination campaigns that eventually eradicated the disease. After earning a certificate in public health from the University of Western Ontario, she decided to move on from her hospital job.

“Healthcare in Canada changed so much during Aunt Jean’s career,” says Paula. “In the 1950s, there was no provincial health insurance, for instance. If you couldn’t afford healthcare, your only option was to seek help through organizations like Rotary Clubs.” The lack of adequate care available for disabled children inspired a group of Rotary Clubs to establish the Ontario Society for Crippled Children in the 1920s. The success of its principal fundraising campaign, which involved selling special stamps each spring, later inspired the Society to change its name to Easter Seals. The organization was the first to employ nurses such as Jean to provide home-based care and to educate the families of disabled children. In addition, Jean often spoke to Rotary and Lion’s clubs to help raise money. The job involved moving to Ottawa. Not long afterwards, Paula’s family moved to Manotick, once a small town but now an Ottawa suburb.

“Throughout my childhood and teenage years, Jean had an apartment in the city and regularly hosted me and my brother Kevin for weekends,” says Paula. “We’d swim in her building’s pool and she taught us to ski. In some ways, I idolized her and the life she led. She had lots of women friends who were professionals and they’d have dinner together, play bridge and go skiing. We always looked forward to seeing Aunt Jean.”

After university, Kevin moved west and pursued his passion for skiing, while Paula and Jean grew closer. Over time, Paula came to recognize how different her life was from Jean’s. Women of Jean’s generation had fewer career options, for instance. And those who did pursue careers were often expected to abandon them to marry and have children.

“Jean often told me: stay in school, go to church and avoid boys,” says Paula. “She’d had a boyfriend when she was younger, but said he was boring and wasn’t going anywhere, so she left him.”

On many of their weekends together, they’d be joined for dinner by one of the disabled children Jean worked with. The experiences stirred up something in Paula.

“It felt natural and normal to care for someone who’s unable to care for themselves,” recalls Paula. “That influenced my decision to go into nursing.”

Jean later worked at the Ottawa Crippled Children Treatment Centre, the first building in the complex that today includes the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO). As with Easter Seals, the Centre later acquired a less offensive name. Once Paula completed her RN training, Jean helped her get her first job at CHEO.

As the careers of both women blossomed, their weekends together grew less frequent. Paula married. When she became pregnant, Paula called Jean to share the news, only learn that Jean also had news to share.

“Jean had met a man she was fond of,” says Paula with a smile. “Lloyd Wright was a high-school teacher and a few years older than Jean. He was also a widower and a Veteran of the Second World War. Everyone in my family was so happy for her!”

The budding romance introduced a new aspect to Jean and Paula’s relationship.

“Jean turned to me for advice about relationships,” says Paula. “After all, romance was new to her. They married when she was 52 years old.”

Jean and Lloyd enjoyed 36 happy years together and travelled extensively after both retired. Paula, along with her husband and two children, hosted them regularly for special occasions. Jean and Lloyd eventually moved into a retirement home. When they were no longer able to care for one another, they moved into the Perley Rideau, where Lloyd passed away in 2017.

Now 91 years of age, Aunt Jean leads a quieter, simpler life. She paints and sculpts in the Perley Rideau’s arts studio, plays cards with other residents and video conferences with Paula at least once a week.

“When it comes to anything related to healthcare, Jean’s mind is still sharp,” says Paula. “Getting the COVID-19 vaccine made her reminisce about giving the polio vaccine to children more than 60 years ago. It’s fitting that someone who did so much to care for others should now receive the best of care.”