A Life of Adventure, Love and Service

The account of Jack MacKenzie’s adventures fills a book—a coffee-table book he produced that chronicles his amazing escapades. His postretirement adventures include skiing to the North Pole, convoying across China’s Gobi desert and twice travelling around the world.

During the Second World War, Jack served as a radio operator and navigator, flying to many remote and exotic locations, occasionally cheating death along the way. After the war, Jack played an instrumental role in the establishment of the Canada Pension Plan, and the Social Insurance Number.

Today, as a resident of Perley Health, the only adventure he craves is a visit with his recently born great-grandson.

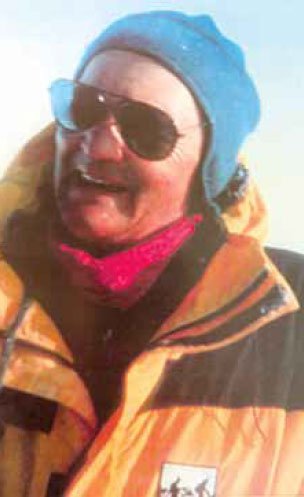

Jack on one of his many Arctic adventures.

Jack on one of his many Arctic adventures.Born Glenn Jackson Mackenzie into a family of 10 children in Quebec’s Gaspé region (New Richmond) in 1921, Jack was bitten by the adventure bug early in life. As a child, he liked to sleep in a backyard tent. There, he’d curl up with a crystal radio and tune in the outside world.

“I’d listen to WJZ New York and other faraway stations,” he recalls. “That’s where I first heard Lowell Thomas, the broadcaster and author who popularized Lawrence of Arabia. His adventure stories excited me to no end.”

Jack soon began to experience a few adventures of his own. His father was a customs officer and the Gaspé was a popular way station for smugglers during American Prohibition (1920-1938). Alcohol from St. Pierre and Miquelon (off the coast of Newfoundland) would make its way into Maine through rural Quebec and New Brunswick. Local authorities once seized the boat of an alleged smuggler and needed an inexpensive way to keep constant watch over it until the case was resolved.

“I have two fine strapping sons who’ll guard the boat by living on it,” Jack’s father told the authorities. Even though the ship never left the dock, living on it fed Jack’s youthful dreams of adventure.

He often swam off the boat with a young Réné Levesque, the province’s future premier. The court case collapsed, the boat’s owner died and the ship sat there for decades, a regular target for scavengers.

After high school, Jack decided to follow in the footsteps of his older brother, who worked at the Bank of Nova Scotia. But his career, like that of so many other Canadians, was interrupted by the outbreak of war. Jack, along with three of his brothers, enlisted, served overseas and survived. “Not many families were so lucky,” Jack muses.

Jack wanted to fly and became part of the Commonwealth Air Training Plan, the largest undertaking of its kind in history. Thousands of pilots, navigators, radio operators and support personnel from around the world trained in Canada.

Jack trained as a pilot at St. Eugene, Quebec (near Hudson), but his landing skills weren’t sharp enough to qualify. He became a radio operator and navigator and reported to a newly formed Army co-op squadron, at RCAF Station Debert near Truro, Nova Scotia.

During the war, he flew in a long list of aircraft—Lysanders, Liberators, Dakotas, Flying Fortresses—in a remarkable array of missions, such as artillery spotting and evacuating wounded soldiers. Jack also flew across the Atlantic dozens of times as part of Ferry Command, transferring North American warplanes to Europe. Those flights etched a line into his face from the oxygen mask he wore.

“Ice would form around the edges of the mask and there was nothing you could do about it,” he recalls. “With no heaters working in the aircraft, it’s the coldest I’ve ever been in my life. We’d do anything to try and stay warm.”

On several occasions, Jack’s crew had to contend with one of the world’s most hazardous landing strip, in Narsarsuaq, Greenland (BW1). In 1941, the Americans built a steel-mat runway on a glacier at the head of a fjord. The approach is virtually surrounded by high mountains and the runway lies on a 20-degree slope.

“The weather is usually bad there, too,” says Jack. “One time, storms raged for three or four days, and we had to wait it out alongside dozens of other crews. Flying out was no picnic—pilots had to climb continuously and steer through the fjord to reach open ocean.”

On one trip, flying a Fortress to Europe, a generator failed, forcing the crew back to Newfoundland. The landing gear then failed to deploy and the plane was ordered first to Montreal, then on to Ottawa (Rockcliffe). There, they circled until the fuel level was low enough for a belly landing.

“Everyone was fine, but the plane suffered a few injuries,” Jack says with a laugh. “They repaired the plane and sent it off to war again.”

Jack and Nan in 1946

Jack and Nan in 1946At an RCAF dance in Ottawa, he met his future bride: Nan (Annie Nairn) Watson, a secretary originally from London, Ontario. They wrote to each other regularly—“She was my gal,” says Jack—married in 1946 and eventually raised two sons, Richard and Jeffrey.

On VE Day, Jack happened to be picking up mail from Rockcliffe. “I had a few drinks that day—many of us did,” he says with a smile. Once decommissioned, Jack vowed that he was done with flying: he had logged about 2,000 hours in the air.

“At the time, there was a severe housing shortage in St. John’s, so my wife and I decided to build a house. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation sold lots in St. John’s,” Jack says. “Nan and I were the first ones to get a CMHC-backed mortgage in Newfoundland. The house we built is still there.”

Following the election of Lester B. Pearson’s minority government in 1963, Jack was assigned to the team that established the Social Insurance Number (SIN) and Canada Pension Plan (CPP). “We set up offices across the country with huge numbers of typists to register everyone for a SIN,” he recalls.

“Many people were against the idea. It was the era of the Cold War and some thought that registering citizens was something only the Soviets would do.”

Jack became the first executive director of CPP in 1966 and retired a decade later. To celebrate, he and Nan embarked on a five-week, 17-airline trip around the world. They continued their travels until Nan passed away in 1995 and Jack thought his adventuring days were over. In fact, they had only just begun.

Jack Mackenzie at the North Pole in 1999

Jack Mackenzie at the North Pole in 1999Astute investing enabled Jack to afford a wealth of exotic adventures. He sailed around Cape Horn aboard the Pacific Princess, drove a Chinese-made jeep across the Gobi Desert, and sailed 1,000 miles up the Amazon River. Later that year, he met renowned Arctic explorer Richard Webber, who planned to lead a skiing expedition to the North Pole.

As luck would have it, the United Nations had designated 1999 as the Year of the Older Person.

The expedition, known as the North Pole Dash, saw Jack cross country ski and camp for seven days. Aged 77 years, 10 months and 13 days, Jack MacKenzie became the oldest person to ski to the North Pole, gaining him a place in the Guinness Book of World Records. His only regret? “They wouldn’t let me pull a sled,” he says with a glint in his eye. “I tried to convince them I was strong enough, but they wouldn’t listen.”

Jack’s thirst for adventure travel took him through the Northwest Passage in 2001 aboard the Russian icebreaker Kapitan Khlebnikov and around the world again in 2005, this time aboard a chartered jet. In 2006, he fell and injured his knee while on aboard a ship anchored off Cambridge Bay in Canada’s Arctic. He developed complications and never fully recovered.

Although forced to scale back his adventures, Jack continued to live independently until earlier this year, when he moved into Perley Health. Surrounded by mementoes of his travels and the book he produced in 2014, Jack still bristles with energy and shares tales of his escapades with a glint in his eyes and the enthusiasm of a teenager.

“I hope my grandson brings his son up to visit me,” he says with a smile. “I don’t think I’m able to travel down to Milton and I really want to meet my great grandchild.”